00. Decoy Pigeon.jpg

“Decoy Pigeon” follows Adaptive Radiations Working Group (Mica Cabildo and Curtis Cresswell) on a roadtrip through the Pan-Philippine Highway and the spotty digital landscape of the Philippine archipelago in search of digital and material ‘duplicates’ of objects in the Philippine collection of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum. ARWG collected and attempted to exchange these duplicates for other digital and material objects with local communities and travelers they encountered during their journey. Mica and Curtis performed ethnographic fieldwork and enacted internal dynamics of research and informant, while simultaneously reflecting on their individual positions as participants in neocolonial forms of cultural exchange through their activities as online artist-in-residence (Mica) and digital nomad/backpacker/volunteer (Curtis). In “Decoy Pigeon”, ARWG collected, shared and exchanged objects, stories and experiences with those who may otherwise have not accessed the Philippine holdings in the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum. Their travels and insights are documented in the following folders as field notes, photographs, and a Decoy Collection.

Adaptive Radiations Working Group focused on a Bagobo wooden bird sculpture labeled ‘Locktaube’ or ‘decoy pigeon’ and thirty-eight other objects from North Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao acquired by the Museum in 1913 as ‘duplicate exchange’ with Rijks Ethnographisch Museum te Leiden, the Netherlands (part of the larger Lot 1913/26). Aside from engaging specifically with this set of objects, ARWG looked into duplicate exchange as a “widespread practice to fill gaps in collections”, and examined other forms of exchange recounted by collectors, curators and mediators during their interactions.

March 30-May 14, 2023

Curtis Cresswell:

The term ‘digital nomad’ makes me sound like I’m running on battery power. I don’t, but it’s definitely a privilege that I’m able to call myself that. My privileges are a part of me, and despite having an alternative set of them while travelling, they will be with me in some form, forever, wherever I go and whatever I do for a living.

Three privileges drove me to The Philippines initially:

Surface level points aside, I’m not blind to the fact my privileges inside and outside of the Global South are rooted in colonialism, and the residues they leave behind.

The obvious examples include; having people translate their language to mine, having more disposable cash than I would in my home country, locals wanting to show me around and befriend the foreigner if even for a few minutes. I even feel some exemption from certain security measures, like the way mall security rarely check inside my bag as I enter.

Voluntourism gets abused at times, by both the traveller and the host, so I wanted to increase my awareness of certain power dynamics throughout my travel, be more selfless, and try not to contribute to anything that would hinder the chance of paid labour for a local as part of my exchange. I don’t yet know if all of these things are even possible though, they’re a lot easier said than done.

Aside from trying to work that out, I feel that collaborating with Micas ‘Adaptive Radiations Working Group’ on RJM’s Leaky Archive project is a firm step in the right direction.

Mica Cabildo:

Online artist residencies are my favorite kind of residencies. I can choose where to live, what to explore, who to work with, and how to work on it. It’s always a great privilege to receive international support to pursue projects in the Philippines, not only for the funding that goes a long way in the local economy, but also for the professional validation that comes with such grants, and the chance to share some personal revelation about my culture and country of origin.

I’ve undertaken on-site residencies in Europe and East Asia, and despite the intense work and illuminating experiences, I was never without discomfort, perhaps due to some internalized racism and deep-seated insecurities about being Filipino.

Nevertheless, coming from a country in the DAC list of ODA recipients, my nationality makes me eligible for certain kinds of funding and support. In recent years, I’ve likewise benefited from the emerging interest in Southeast Asian art, tropical regions and (in the case of Leaky Archive) the global south, although I attribute a large part of my luck to a willingness to engage in a very specific, very Western way of speaking, thinking and participating in the contemporary art world.

Before embarking on Decoy Pigeon, I was living in a small surfing town in Zambales on the west coast of Luzon, researching on the 1991 Pinatubo volcano eruption and solar engineering for Akademie Schloss Solitude’s 18th Web Residencies. I had been acquainted with Sang, the local tattoo artist, for a couple of months by this time, although I was putting off my desire for self-ornamentation until the end of the residency. I had with me several handmade tank tops which I obsessively crocheted and accumulated over the past two years, and in the end, I traded two of these for a small firefly tattoo. This exchange was the initial inspiration for the duplicate exchange idea of “Decoy Pigeon”.

Curtis and I met in January and left Zambales in February to travel around Luzon and were already on our sixth stop when “Decoy Pigeon” was selected for a Leaky Archive fellowship. Tattoos later became a recurring motif in our travels.

March 30-April 04, 2023

Curtis:

The northernmost sandy beach in The Philippines, and nicknamed the coastal paradise of the North. It appears as though a tourism boom had been on the periphery for a while, but it never really got there despite the town sitting on the AH26. Perhaps due to its physical location, sandwiched deep between more accessible tourist spots.

Pagudpud draws in a lot of visitors to the North west, perhaps those visiting Vigan choose to venture further up the coastal highway for their beach fix. For those more on the North East in Cagayan valley or in Apayao, areas like Santa Ana and Palaui Island are more accessible.

Tourism aside, the town and its lush landscape felt modest. Walking towards the main town and back we would have a view of the Lakay-Lakay (old man), a rock formation which gets its name from the legend of a wealthy old man who was cursed and turned to stone for not sharing his fish with a less fortunate neighbour.

To this day, the town has a firm stance on illegal fishing, and many fishermen passing the Lakey-Lakey still throw a fish from their catch back into the ocean, giving back to the sea that provides them with the ability to sustain a vibrant fishing trade and plenty to eat. They believe this protects their town - a humble testament to how little they actually need the tourism to fuel their local economy.

I’ve got a little more used to people staring at me for being so far off the gringo trail. The women like to ask where I’m from, and some giggle when I try to speak Tagalog.

The groups of children and men like to make dude-slurs like “sup bro” and whisper ‘Americano’ among themselves while staring. I haven’t yet had the guts to tell them I’d prefer a Cappuccino.

Some kilometres off the shore of the town, Fuga Island can be seen on a clear day. That said, it’s not clear to me what happens on this island. On one hand, it has been described as a playground for Chinese investors, who are trying to establish a smart city and take advantage of its position within Cagayan’s Special Economic Zone. But on the other hand, it’s a place for US-Philippine ‘Balikatan’ operations to take place, which are military drills undertaken in the escalating tension between China, Taiwan, and the US. What is clear of this island is how neocolonialism has allowed a grey area in domestic politics to develop, and left the island between a rock and a hard place - US military aid and Chinese money.

On our final day here, we had the pleasure of meeting our host’s husband, who had been running for local Congress the previous year. We were saddened to hear how the corrupt oppositions would buy votes and use intimidating tactics against the locals to influence their decisions. Hearing how this affected the host and her husband, while they kindly gave us a tour of their home and local beach, could have darkened my rose tinted view of this quaint northern paradise. But, while they both laughed and joked about the number of friends and family they’ve lost throughout the process, I found it somewhat difficult to feel too sorry for them.

Mica:

Claveria was a last-minute decision as we tried to find a manageable stop between Pagudpud, Ilocos Norte and Tugegarao, Cagayan. We stayed in an airbnb run by a popular local cafe called Caferiano, with a picturesque view of the sea and our first unobscured view of Philippine sunrise. Caferiano also runs Artkultur, a small art space that hosts summer art workshops for local children. I considered contacting Artkultur to see if they can host an exhibition or trading activity for Decoy Pigeon in the future.

Our lodgings was a shipping container converted into a bunk-bed room with air-conditioning and dedicated high-speed internet, which made for great temporary headquarters and refuge from the midday sun. Curtis and I were nervous about our first meeting with Agustina and the Leaky Archive Fellows, so we spent a few days reading up and preparing for the call. After the meeting, we breathed a sigh of relief and joked about how Agustina and the fellows must have felt about suddenly having a white British man in a fellowship specifically designed for artists from the global south.

I had recently done a project about John Whitehead—a British ornithologist credited for first describing the Philippine eagle in the late 19th century—and wrote a short compilation of letters responding to Whitehead’s Philippine field-notes. I found this collision and eventual entanglement of cultures to be an interesting area to explore, so when the opportunity arose, I invited Curtis to be part of of the second iteration of ARWG for Decoy Pigeon and Leaky Archive. We traveled and worked well together, and I felt that his insights as a modern-day explorer and temporary transplant would add an interesting perspective to a project on decolonizing ethnographic collections. I was likewise interested in how our internal dynamics and personal relationship as British and Filipino would take shape during this three-month journey.

April 04-11, 2023

Curtis:

It was Mica’s grandfather’s birthday, a great time to meet the family for the first time. Many of them spoke to me in my language, and gave us travel advice. We then made an unexpected decision to join Mica’s family for a night on their trip to Buscalan in Kalinga.

We returned to Tuguegarao to spend Holy Week away from the resort crowds. Throughout our time here we had plenty more family time, and witnessed a Holy Week procession on Wednesday, which involved hundreds of people gathering at the Church, and holding a march ritual. The march covered a large area and returned to the church, carrying around 50 floats depicting biblical figures and telling the life and death of Jesus. Mica told me that in certain towns, they perform real-life nailing of devotees to the cross (Flagellation), to imitate Jesus’ suffering.

On the Saturday we then went to Calvary Hills, where we saw lifesize figures depicting Jesus journey with the cross from carrying to the crucifixion.

April 05-06, 2023

Curtis:

Throughout the car journey we were both in awe at the proud landscapes offered by the Cordillera Region.

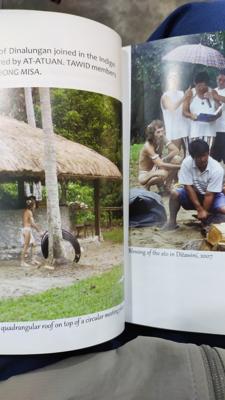

We were on a quest made by many tourists, both local and foreign, to either observe or obtain Batok tattoos, a tradition that’s been maintained throughout colonial eras, by one of the only tribes in the Philippines to have avoided direct foreign rule. The 106 year old tattoo artist (Apo Whang Od) who has risen to fame being the last artist to have tattooed the headhunters, and only female artist of her time, awaits tourists who make the pilgrimage through the winding cliff roads and hike through the rice terraces to her village.

Once we’d parked the car, our tour guide escorted us up to the entrance of the village, passing many souvenir shops that contained crafts worthy of making our shadow collection. Before physically entering I was approached by a loud solo traveller. Despite seeing him in the car park when we arrived, he had already completed his experience of Buscalan in a flushed yet very hyper state, after racing up the mountain, getting his new tattoo, and preparing to race back down. “Look, my new tattoo!” he shouted, then pointed at an elderly man screaming “LOOK. There, that’s her brother!”. I was then made to pose with the elder for a photo, before having my Instagram handle screenshotted, so he could send me the photo when he returned to 5G territory (I never received it). Throughout the time that this occurred, my Filipino girlfriend and her family were not even acknowledged. This became something of a recurrence, which I was blind to until the following morning.

A few days before our trip, Apo Whang Od appeared on my Instagram feed on the front cover of Vogue Philippines, probably because I’d been looking through tattoo related content for the past month. The cover was titled “Next Of Skin”, referring to how the tradition has been passed down to her younger family members, now apprentices. She is a celebrity after all, but I wonder how many people will make the pilgrimage when she’s unable to create her art, what will happen to the local economy, souvenir shop owners and tour guides if she’s no longer able to tattoo people. They will have to market the lesser known artists of the village (there are over 200 in total, afterall).

Mica and I reflected on how Apo was crouched down each day, tattooing the same 3 dots on sometimes hundreds of people, many of whom would not think to thank her as they admire their new tattoo and have her pose for a photo with them. But she is, as Mica puts it, “taking one for the team”, and providing so much for her community by committing her life to her art and keeping the local traditions of her region alive.

Between getting ourselves inked, we purchased some souvenirs and introduced the concept of Decoy Pigeon to Mica’s family. Our tattoos were also souvenirs in a way, a commoditised version of something traditional and spiritual for Kalinga tribes.

Did we think that the tattoos we’d collected would be carried with us into the afterlife? Maybe not but I can’t speak for all of us.

Have I appropriated this side of Filipino culture by carrying through this transaction involving tribal tattoos? I’m not Filipino afterall, but if members of the tribe are willing to tattoo foreigners, then I believe it’s okay. I haven’t indulged in the commoditization of the tradition any more than the Filipinos who aren’t from the Kalinga tribe, and the power dynamics between the tourists vs artists who need to make a living, remains the same regardless of where the tourist is from.

Similar to the decolonising of collections, I feel that both local and foreign tourists should have a duty to understand and promote the traditions and cultures they have borrowed or collected from. Whether we have obtained souvenirs, photography, literature, tattoos or experiences - we should take the responsibility to hold onto the wider appreciation of such origins, without profiting from or exploiting them, and ensuring each exchange is made on fair and transparent grounds.

April 11-16, 2023

Curtis:

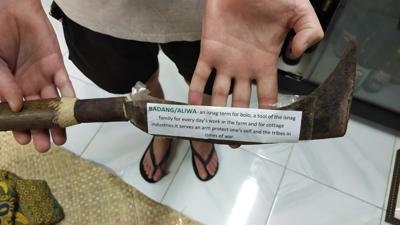

We arrived in Apayao, the northernmost Cordilleran province, to lookfor replicas of the wooden shield and the headhunter axe from the Isneg tribe. We spoke with tourism officers at the Luna DTI (Pasalubong Center) about the axe and discovered that there are two similar versions, an Aliwa for men, and an Iku for women. Both were used in harvesting, and for the men also self defence, but are now just handcrafted souvenirs/gifts, and used sometimes to open the betel nut for those who consume it. We were thankful for their advice, and for the free tasters of sugar cane wine, Basi, and allowed them to take a photo of us for their socials.

We then proceeded to the The Luna Eco-Tourism centre, where the officers were very glad to have visitors, as they struggled to get many travellers pass through especially from overseas. They gave us a lot of advice for visiting their natural attractions, and also had a small collection of crafts and donated artefacts which they let us explore. We found some spears, shields, and a range of Aliwas/Ikus, but they were too large for us to collect physically. We bought some Basi and gave a tip to show our appreciation.

The following day we got a tricycle to Pudtol in search of a giant aliwa monument we’d seen online, so we could get a photo with it just in case we struggled to find a physical version to collect. We bought our tricycle driver some lunch as a thank you before asking him to take us to our final stop.

Isagaddan Crafts & Souvenirs features a small craft store containing a range of handmade gifts, and a cafe which used some traditional Isneg words in their menu.

We found bows and arrows for sale, and photographed some spears similar to those from Luzon (unspecified). The crafts woman told us about the headdresses she makes, similar to a Tinguian item (29811), but they had all been bought by local schools due to a festival taking place the previous month. She also informed us that they are not a standalone accessory, but rather they are paired with a traditional headband to keep it in place, and worn only in certain ceremonies and rituals. We bought some aliwa keyrings, and a small iku with similar sizing to the one in the RJM collection.

April 12, 2023

April 13, 2023

April 13, 2023

April 16-20, 2023

Curtis:

We tried to visit the museum in Rizal Park but it had closed temporarily, and didn’t open the entire time we were there. We spent more time with Mica’s family, sometimes watching TV with her grandfather.

The Balikatan military drills often featured in the news, and the rising conflicts between China and Taiwan. We discovered that during the week that we’d left to visit Apayao, there were protests taking place in Rizal Park against the US military presence. Activists such as the League of Filipino Students attended, who highlight that the US presence creates a feeling of security in the general community, but shifts focus away from the existing residues of US colonialism such as exploiting raw materials, land rights, cheap labour while being less accountable for crimes committed by their servicemen. These issues are all too familiar for many other post-colonies around the world, and, like the Filipinos, I expect there is a large split between the communities who support and oppose military aid, along with other lasting ties they have with their colonisers.

Mica:

We agonized for days over our next move: either we continue south on the east coast to Isabela and make it all the way to Baler, a surfing town on the Pacific coast; or head back up and down the west coast the same way we came, to visit big museums we skipped in Ilocos and arrive in Abra, where we hoped to find the Tinguian bulk of the Luzon artifacts. A hazy third option almost presented itself, a way through the treacherous roads of the Cordilleras, which would take us straight to Abra, but it was too vague to pursue. In the end, we decided to take the safe option and retrace our steps to the west coast and visit some familiar places and faces along the way.

April 20-23, 2023

Curtis:

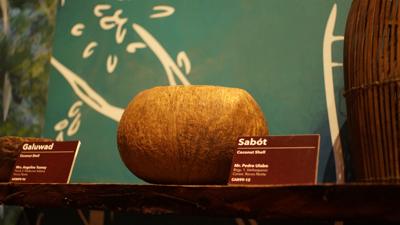

We passed back through Pagudpud for 3 nights, which is where we were previously when we discovered ARWG was chosen for the Leaky Archive Fellowship. But the town doesn’t hold many cultural sites or museums, so we didn’t have much to do for the project. We did manage to find a Buyubuy (coconut cup) at IMA Cafe near to our accommodation, which had many local crafts on offer including bags, jewellery, mats, food and beverage.

April 23-26, 2023

Curtis:

We visited the Ilocos Norte Museum which had some great collections of items, interactive stands and colourful murals to better personify the collection and help bring it to life. We saw an octopus loure from Currimao which resembled the purpose of the Mindanao Decoy Pigeon, as well as spears and shields similar to those in the RJM collection. There was also a bag made from a carabao horn which resembled the drinking horn we were looking for (RJM item 29817), however as it featured a lid then we can assume it’s more for storing things rather than drinking from.

We contacted the Mariano Marcos State University to request a visit to their College of Teacher Education Taldiap Society Museum. We found their Facebook page when searching for Museums within Laoag and they have a much larger following than the public museum.

In comparison, their Facebook content showed a large number of cultural projects and activities carried out by their society, such as celebrating national heroes, heritage and preserving identity for the students through art and ceremonies.

The student museum officers were enthusiastic about our visit and kindly provided us with a tour of the collection. They gave demonstrations, and showed how items were used compared, which felt more engaging than the public museum.

Because they call themselves an ‘open museum’, they build their collection by accepting donations from students, so we saw potential to make an exchange, and introduced them to Decoy Pigeon. They have around 300 items themselves, but still seemed surprised when hearing the size of RJMs Filipino collection. We think it’s great to have the students involved in the collecting of items, as it gives them a chance to engage with the owners of the items, and even bring personal stories of their own to the museum.

April 24, 2023

April 25, 2023

April 26-29, 2023

Curtis:

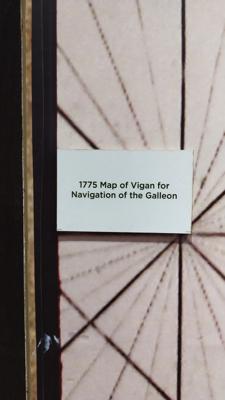

Vigan City was made an official UNESCO site in 2012 for being “the best-preserved example of a planned Spanish colonial town in Asia”. While the city has preserved so much of its rich history, they most likely receive most of their visitors based on the old colonial style buildings rather than their pre-colonial history. This is reflected in the number of museums dedicated to national heroes of the colonial and independence eras, the contents of the Conservation Centre and the souvenir shops.

We looked for the traditional wooden comb (item 29810) in souvenir shops and antique stores, and had asked owners if they’d ever seen them in Vigan. Our time spent on Calle Crisologo and the surrounding streets was interesting, and we browsed a range of handcrafted gifts and antiques from WW2, but our search was unsuccessful after all.

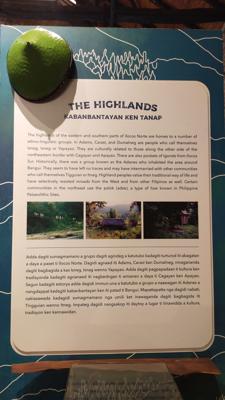

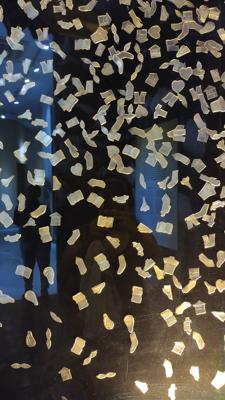

On our last day we visited the Conservation Complex, a new project that teaches visitors the history of Vigan. The first building featured a small pre-colonial section, but focused mainly on the Christian faith and colonial / post colonial transition. Despite this it did introduce us to the Tinguian tradition of placing large stones at the front and back of the village to represent their protecting guardian.

In the second building there were some interesting displays on the architecture, construction, preservation of the heritage buildings, along with an interactive game. At the back, there was an area with spare parts of windows and doors, which they sell to owners of the colonial homes who require repairs.

April 26, 2023

April 27, 2023

April 29-May 04, 2023

Curtis:

On our first night in La Paz we settled in with amazing views of the hills beyond the Abra River. Our host, Amarte, was keen to hear about our project over some Basi Wine, and we shared our experience in Laoag and Vigan.

We told him that the Gabriela Carino-Silang Gallery was on our list to visit originally, despite being a personal collection containing items from many cultures outside of the Philippines. We couldn’t visit though because the contents were mostly destroyed in the 2022 earthquake, but he recommended that we get in touch with a local blogger, Dave (Silverbackbacker), who had moved to Abra from the UK, and knows the person who had inherited the collection. He allowed us to invite Dave for dinner the following night.

Amarte then decided that he’d put us in touch with his former college ‘Divine Word‘ (DW), as he’d remembered they have a small museum which features items similar to the ones we’re looking for.

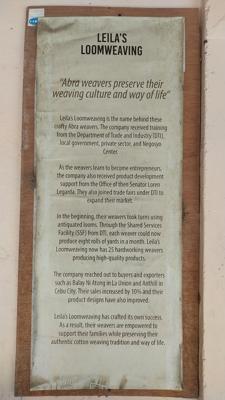

The next day Amarte took us to the Lusuac cold springs before heading to Leila’s Loom Weaving. We discovered the Piningitan design almost straight away, which Leila informed us takes months to create, despite it appearing like one of the more basic designs.

She gave us the name of the various textiles, and told us that the scarf design (29806) was from the Manobo Tribe, slightly south of Abra, before showing us the production rooms and allowing us to take photos of her next to the equipment. There was nobody weaving when we entered because it was a Sunday, however there were so many amazing designs just halfway through production, and we could see how intricate and mathematical the process was. Her employees are all locals, so they tend to come and go as they please, picking up their designs and adding a little to where they left off. Before heading back out we thanked her, and bought a few small coin purses that were created from cut offs.

Later that night we met Dave the blogger, who informed us that it was quite hard to be granted a visit to the Divine Word museum, and that he’d tried three times already. We were lucky enough to have heard back from them though, so we prepared a letter to the president Father Gill. We were probably more likely to be allowed entrance due to having a commissioned project, which we’d outlined in our letter to the president. We also discovered later on that they’re trying to pursue their own initiatives of collaborating with external researchers and get involved with projects outside of their own establishment, which probably helped our case further.

We enjoyed some more Basi Wine with Amarte and Dave, watching the lightning strike over the hills. Dave also informed us about where we might find a pan flute, crafted by a musician who is renowned for his products and songs (Elmer Tadeo). It dawned on us though that the possibility of meeting him was slim, as we’d need our own transport to reach where he is, and also, there’s no mobile service in the town that he lives in. As Dave put it, it’s like you have to send a pigeon to arrange a meeting with him - in other words, it’s more a case of sending a messenger rather than contacting him directly.

Dave and Amarte also informed us that we’d struggle to find item 29816 (the three drinking vessels attached to each other) in a collection. They are usually kept individually, but may have been attached together for transportation either by the owners or by the collector, so they don’t often appear as a trio. While this type of vessel is still used today in rural communities and by their farmers, they are generally more of a disposable item, so we’d have better luck discovering discarded versions by searching in bushes rather than individual collections.

We were told that if we had time, we should try and visit Tayum church, which came into our conversation about the Tinguian tribe. The church was closed after the recent earthquake made it dangerous to enter, but interestingly enough, Dave told us that the Spanish built the churches with the addition of swirling sun symbols, so it would not only appeal to Tinguians, but would make them worship the church without fully acknowledging it. This is one example of how Tinguian beliefs were slowly warped out of the community, so that Christianity could become the dominant religion, where it has been now for over 500 years and has a large presence in Philippine politics and their national identity. We noted this as another form of decoy associated with colonial exchanges.

The next day we were given access to the DW Abraeniana Institute Museum, which in it’s own words, “is the foundation dedicated to the study, preservation and promotion of Abrenian culture, history, literature, language and the encouragement of indigenous liturgy, catechesis and theological reflection”.

Father Gill (the college president) and Dr Pambalan (Research Director of Abraeniana Institute) were both interested in our project. We waited roughly two hours before entering the Museum, and in the meantime, browsed some of the official Abraeniana Annual Journals which we later purchased as they contained some interesting chapters about the local Tinguian culture.

We were kindly given a tour of the museum, many of the items we were already accustomed to, having seen similar ones in various other museums, although there were noticeably more clay pots, labelled with various Chinese Dynasties. This led us to ask about how they’d obtained their collection.

The artefacts were given mostly by the priest who’d set up the collection initially, and contained some donations. We also discovered that some of the items were local family heirlooms, sold to the priest at times when the families were struggling financially, and interestingly enough, also exchanged at times, in return for excess to education.

Father Gill also explained that we can’t take photos of the collection, out of respect to the original owners of the artefacts, and those featured in the photographs. There are discussions of whether or not they can one day get permission to make the collection digital, published online to increase accessibility. This would be a lengthy process, so as of today the collection is only accessible to DW students. We feel their approach is responsible, and we respect their decision to impose this rule - we were very lucky to have been given access physically and hope they can eventually open their archives beyond the walls of DW College.

On our final day in Abra, Dave had kindly arranged for us to meet a local filmmaker and actor, Dexter Macaraeg, who creates short films aimed at sharing and preserving Tinguian culture and traditions. Dexter was keen to help us with our research and enjoyed hearing about the project. We mentioned that the artefacts were obtained through exchange with a Dutch museum, and were surprised when he asked us whether it was a Leiden Museum who had been involved. We later discovered that Dexter was aware of the Leiden Museum after researching traditional Tinguian designs during a personal dressmaking project he’d undertaken. It was very coincidental that the main book he’d used for inspiration and research (Embroidered Multiples) was created by the Leiden Museum, containing solely Filipino garments from their collection, which were, as he put it, “looted”. We don’t know the method of which the garments were obtained by Leiden, but it’s clear that Dexter feels that they were somewhat stolen. Whether he means literally or symbolically was not discussed, but the sentiment was not positive.

As an advocate for the traditional attire, Dexter was enthusiastic about the textiles within the collection, when showing him our PDF containing the items from RJMs exchange. He told us that we might find more information about the Manobo scarf by visiting Joy, a local seller of traditional clothing at Achilles 25, so he contacted her to arrange a visit to the store.

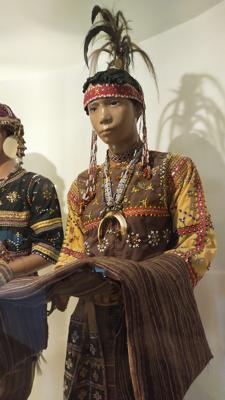

Joy’s shop contained many handmade items like jewellery and other accessories, along with items of clothing - some of which she’d sourced from Leila’s Loom Weaving. Joy, like Dexter, was very interested in our project, and wanted to help in any way she could. After we had some photos with her, Dexter found a lot of enjoyment in dressing Mica in everything from the Piningitan to a bamboo hat, and I discovered a feather headdress near the front of the store, similar to item 29811.

Joy, passionate about helping us, recognised the design we were looking for and confirmed for us that it originates South of Abra in Manabo. Dave and Dexter were eager to take us there the following day, but our schedule didn’t permit unfortunately. Interestingly enough though, Joy actually had a photograph of herself wearing the same garment with the Manobo pattern featured in RJM’s collection, and allowed us to take a photo of her screen, as a way of collecting a digital duplicate of Item 29806.

We then went to lunch with Joy, David and Dexter, where we shared a large amount of local dishes, and Dexter told us more about his film projects and community engagement. After having the day to reflect on our project, he started to share a story about a recent visit to a celebration held by one of the local indigenous groups. When telling us about their talent show and performances, he expressed both humour and frustration about young members of the group singing a popular Disney song from the movie Frozen:

“I asked them to do one of their (traditional) songs instead, not something from Disney. Something cultural, that’s who they are… and that’s their talent… and that’s decolonization”.

It was great to hear Dexter’s point of view, and his opinion on how he ensured his own collection of experiences were decolonised. As I understand, he hadn’t requested a traditional song simply for his own listening pleasure, but to also enforce the need for youth within indigenous tribes to carry their traditions forward into future decades - a message featured in one of his films named Am-Amma. Dexter explained that Am-Amma tells more than the story of a traditional cloth design, and further symbolises the need for the indigenous children to continue to discover and hold onto the history of their tribes through the messages woven into their textile heirlooms. It would be interesting to meet more filmmakers, and learn how the Filipino cinema industry has been colonised. As I realise, to this day, they only ever play American blockbusters or similar-styled British movies on the long journey coaches, both new and old Hollywood classics.

Just before leaving Abra, we decided to give one item from our collection to Amarte, because despite being our host, he provided a lot of great advice, put us in touch with Dave and Abraeniana at DV, recognised the design of the textile item we later found at the loom weaving shop and overall was a great help and advocate of our project.

April 30, 2023

May 1 & 3, 2023

May 04-07, 2023

Mica:

After spending several days inland, we were looking forward to being on the coast again, and were very glad to return to the bamboo huts in Ocean Breeze Resort in Baroro, Bacnotan. One of the curators at DWCB Abraeniana Museum in Bangued mentioned a small museum in Baroro, but it didn’t turn up on Google Maps, and our host Dr Neil didn’t know about any museums nearby. The nearest major museum in La Union was further south in Agoo, but because we only had a few days in La Union, we decided to skip it and conserve our energy for Baguio.

During our first stay here in March, we met a little boy who always called Curtis “Bro!” as he biked on the narrow streets outside the resort. It’s a pet peeve of ours, getting “bro” calls, but this boy seemed so sincere and disarming that we didn’t mind. One day, we saw him flying a kite on the beach. He gleefully pointed to his eagle-shaped kite and yelled to Curtis, “Bro! Agila, bro!” We hoped to meet him again, but we didn’t catch him this time.

May 07-12, 2023

Curtis:

On our second day in Baguio we went to an artist village called Tam-Awan, looking for crafts, artefacts, as well as a tattoo artist. After browsing the artwork and souvenir shops we were recommended to a nearby cafe named Igorot Charm Cafe.

Here I received a tattoo from Ate Wamz, who informed us about the many Igorot designs outside of the Kalinga tribe. Because they are similar to, and even share, some of the traditional designs of the Kalinga Tribe (falling under the same umbrella of The Cordillera Administrative Region), there are many modern day politics attached to the ownership of these traditions. Ate Wamz shared with us another side of Buscalan, untold to many tourists who visit there.

Wamz had also received backlash at times from the Buscalan community, because she’s from a different region and offering similar designs. However a closer look shows that Apo herself is also from a different region, and migrated into the Butbut Tribe when she was younger. The heavy commodification of the tradition, and having Apo as the face of it, has caused heavy controversy in the network at times, and also means the other 200+ artists that live in Buscalan are left out of the limelight.

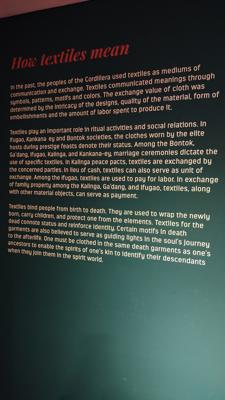

The following day we visited the Kordilyera Museum, which was mainly exhibiting the traditions behind textiles from various tribes around the Cordillera Region, including the Tinguian, Bontoc, Kalinga, Ifugao and more. We discovered that textiles within this region were exchanged at times for goods from other regions, labour, used in peace pacts and at times as payment.

Wamz and her husband Mario invited us to dinner that evening, where we enjoyed some great food and learned about some of the traditions of various Igorot tribes, such as Kalangaya and their loom weaving patterns, rituals and ceremonies. This evening we’d also been introduced to their friend Maynard, who we made plans with to visit Pugad Ni - a local gallery and studio which features some artefacts alongside the exhibitions. The gallery was three or four floors, and housed hundreds of pieces from local artists, and is owned and managed by Art Luzono. The first 3 floors featured many Bulul sculptures that represent the Ifugao rice god, and on the top floor there were some spears and arrows similar to RJM’s. Aside from the amazing art exhibits, the artefacts were obtained through the means of exchange, where Art Luzono trades his own work for items, which then are used to decorate his studio or compliment the work he exhibits.

Some of the items were very personal and somewhat intimate, like funeral chairs and cribs for babies. Some were very old, possibly heirlooms and could be considered museum worthy artefacts. It seems as though the method of collection was on more mutual grounds, with no real power dynamic. Neither party is trading because they want/need money, nor are they interested in how the value may change over time, but they trade out of mere appreciation of what the other person has.

Mica:

We previously visited Baguio Museum during our first stay in the city back in February, but unfortunately the museum was closed this time around due to a power interruption, and we couldn’t take a second look at their collection We did, however, made return visits to the labyrinthine treehouses of Victor Oteyza Community Art Space, Oh My Gulay Cafe and Ili-likha Artists Wateringhole—iconic Baguio art venues built by filmmaker Kidlat Tahimik, his sons and their extended community—and hoped to catch a film at the Sinematik, although the indie cinema seemed to have been inactive for some time. I wanted to watch some Kidlat Tahimik films with Curtis as decolonization inspiration for Decoy Pigeon, so looked for some of his films on Youtube and Vimeo instead.

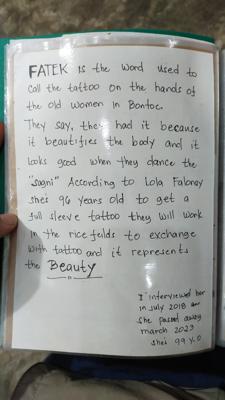

While browsing through Wamz and Mario’s library at Igorot’s Charm Cafe, I came across the concept of whig-whis, a term that today refers to gifts or tokens exchanged among the Butbut tribe in Buscalan. In the book, Apo Whang-Od tells of whig-whis as “memory marks” exchanged between traveling tattoo artists like indelible “remembrances” on the skin.

May 08 & 11, 2023

May 10, 2023

May 11, 2023

May 12-14, 2023

Mica:

Clark was our first stop out of Zambales back in February, and we returned to the same Bureau of Immigration office to claim Curtis’ Alien Certification of Registration ID card that he applied for nearly three months ago. In February, Curtis accompanied me to Holy Angel University in Angeles as I finished my remaining research tasks for the Pinatubo project, and I was impressed by his genuine curiosity and attention to information and displays about the volcano. It seemed appropriate that we ended our Luzon tour in the same city and boarded a flight from Clark to meet Curtis’ father in Visayas.

May 14-June 25, 2023

Curtis:

Cebu gave us more time to reflect on the past months. We found ourselves quite attached to the idea of finding replicas of the museum’s collection, and to the actual items themselves.

Looking back at the exchanges we’ve made since the start of April and the ethics surrounding those exchanges, most of our encounters show different levels of power dynamics present, despite we were not noticing them at the time. But when interacting with people who could provide us with more insight, or even allow us to obtain something towards our shadow collection, we would try to show transparentcy.

For example, there have been times where we’d been welcomed as researchers rather than collectors or customers, in particular, instances where we have introduced the project to the other party. We can assume that in these cases, even if we haven’t gone into much detail, the merchant is aware that we were trying to obtain more than simply a souvenir or piece of information - that there is a wider merit attached to our search such as commission or career advancement. So we have often been asked if we are bloggers too, as people would want to know whether they were going to be critiqued.

But in most cases, people share a mutual desire to help us build our collection and knowledge through interacting with, documenting or even obtaining some of their items. Through their desire to help us, we have even gained access to places that tourists and locals wouldn’t, without being questioned on how or if they’ll get anything in exchange.

Because of the nature of the collection, the places we visit are within the realm of national heritage, culture and identity. The people we’ve encountered are often, by default, passionate in promoting their knowledge, work or collections, and they strive to keep their culture alive. In addition to this, we’re most likely granted some extra privilege due to the fact we’re acting in association with a museum from the global north.

In other encounters, specifically where we are dealing with a salesperson or tourism officer, there is a different dynamic of power, because there is an extra element of customer service involved. Some merchants are often more likely to listen to what we have to say due to their desire to make a sale, whereas Joy from Abra was quite invested in helping us, and even gave us products for free. I feel this was mainly out of kindness, and wanting to share traditional gifts from her local heritage, and much less in the hope that the project would help promote her business.

May 14-28, 2023

Mica:

Curtis’ birthday is on May 23rd and his father Jonny came for an 11-day visit. We took this period of time off our projects to travel to the nearby islands of Bohol and Siquijor with Jonny and celebrate Curtis’ birthday.

Bohol is the home of the tarsier, the world’s second-smallest primate. Every major tourist spot in Bohol sells a wide variety of tarsier-themed souvenirs, some cute, some silly. At the Lemur and Butterfly park, next to the mandatory tarsier souvenirs, were coconut cups like the ones we collected in Luzon.

May 20, 2023

May 28-June 25, 2023

Mica:

It sounds like a plot straight out of an adventure movie or video game, but halfway through our Decoy Pigeon journey, we did, in fact, get stranded on a tropical island while hunting for ethnographic artifacts for a museum in Europe.

We were fortunate enough to find affordable accommodations at Petit Coin de Paradis in Alcantara, a small town north of Moalboal, where we stayed for a month as we took on small projects to pay for rent and daily expenses. Whenever we could put aside enough money, we rented a motorcycle to go to White Beach or explored the mangrove forests of Eskapo Verde in Badian. Towards the end of our stay in the south of Cebu, we finally went on a kayak tour of the mangroves at high tide.

Our financial woes were eventually resolved, but it took us a while recover from the stress and resume our project with the same level of enthusiasm. However, this experience brought up some important questions about our practice: What kinds of projects get funded, who funds them, and why?

This made me think of all the ideas, aspirations and possible futures that did not materialize and all the expeditions that were cut short simply for lack of resources. This also convinced me of the need to be able to pursue creative projects independently.

June 25-July 09, 2023

Curtis:

In a region often stigmatised for recent terrorist activity, lies Davao City, now dubbed as one of South East Asia’s safest cities, with its heavy police and military presence, a reminder of how Duterte’s controversial Death Squad composed his war on drugs and terrorism throughout the region. The bustle and intrigue of the famous night market still welcomed us despite the armed police checking bags upon entry, and their large military vehicles on the adjacent street. Visiting here for BBQ dinners or sugary treats such as Buchi still became something of a daily occurrence.

After a few days in Poblacion, Davao City, we had a short break to visit Mica’s friend, Abba, on Samal Island, and then went to Mati in Davao Oriental for its Subangan Museum (which was closed), and the surfing (for which it was not the season). We then took some time to relax and catch up with one of Mica’s friends from university, before drawing an end to our search for Decoy Pigeon, and the wider range of artefacts, in time for my departure back to the UK.

June 25-30, 2023

Mica:

On the way to People’s Park, we passed the Cinematheque and took note of the film screening schedule, happy for another opportunity for Curtis to learn about Philippine film and cinema. We would later on catch a free screening of Ishmael Bernal’s Manila by Night (1980).

For several days we planned to visit the Philippine Eagle Center in Malagos, about an hour ride from central Davao City, where we could possibly meet some members of the Bagobo community. I have had online interactions with PEC facilitators and their indigenous partners, Bagobo-Tagabawa forest guards from Barangay Sibulan, for a previous project, and we thought this network would be an excellent starting point for our search for RJM29832 Locktaube or decoy pigeon and other Bagobo artifacts. However, in my experience, such meetings need advance preparation and a modest budget, neither of which we had at this point. We didn’t want to show up without anything to offer, and while we were disappointed by the setback, we focused on places we could visit and things we could do in central Davao City instead.

Curtis:

On our first day we visited D’Bone Collector, a three story museum containing a huge collection of animal skeletons collected personally by the founder, and through donations from organisations around the world. The collection is interesting, and draws attention to how some of the animals died through man made causes. This is because the museum also dedicates time and funds to help with rehabilitating ocean mammals, and creates workshops to raise awareness of endangered animals in The Philippines and how they can be protected.

Before discovering the latter, I’d thought the museum was a slightly random dream of a taxidermy fanatic, a hobby that got out of hand. But now I appreciate the wider outcomes of the exchanges made throughout his collection, and wonder what else museums can do to decolonise the items they’ve collected as part of duplicate exchange, or colonial exchanges and looting.

For the bone collector, this means collecting from dead animals, to eventually empower the living ones. For those who profit from pre colonial artefacts, such as museums, this could mean having donations for the regions where the items had originated. Donations could then help towards community engagement projects that preserve and celebrate their culture, and improve cultural education within schools for example.

On the 28th, we paid a visit to the Poblacion Market Central where we’d heard there are traditional craftworks for sale such as clothing and gifts. When we arrived, we were surprised to see there was much more than crafts, but also crafts made by members of the Bagobo and T’Boli tribes both recent and antique. We browsed some interesting items for sale, including detailed brassworks like jewellery, weapons and betel nut boxes. Many of which were created by present day Bagobo and T’Boli, using traditional methods, and decorated with the traditional bells. The store assistant was interested in our project and told us how T’Boli and Bagobo (being recognised as the most decorative and vibrantly dressed tribes of The Philippines) often have inlays on their metalwork designs and are known for being the first to develop these types of decoration.

She recognised the Knife With Sheaf (RJM 29831) from our catalogue/PDF that Mica had created back in Apayao, and thought that she’d seen one at the Davao Museum of History and Ethnography, which is where we were heading next. She also gave us the details of her manager who is more involved with trading. He may recognise the weapons, or the use of decoy birds, and might know where we can find a replica or modern day version.

The Davao Museum had an ethnographic section on the second floor, which contained a lot of great information and items on display, first showing the range of indigenous tribes from the Davao region, before revealing their artefacts. We admired the detailed craftsmanship that went into their designs, and discovered that Bagobo is where many of the designs originated, and they can be found in wider territories of Davao because they were trading their tools and goods with other tribes.

June 27, 2023

June 28, 2023

June 28, 2023

June 30-July 03, 2023

Mica:

Abba, a friend from Baguio and sister-in-law to Kidlat Tahimik’s youngest son, heard we were in Davao and invited us to her hometown Samal. Officially the Island Garden City of Samal, the island is a 15-minute ferry ride from Davao City. The ferries run 24/7 and partygoers from the mainland would sometimes continue their late-night festivities in Samal to circumvent Davao City’s strict curfew.

Abba grew up in Samal and knows the island very well. She works at the Samal tourism office and has many contacts, including tour operators and diving instructors. We joined an island hopping tour with her extended family to the nearby islands where we went snorkeling and cliff diving. The last island on the tour had strange excavations in the rock, allegedly traces of large-scale treasure hunting activities.

(photo courtesy of Samal Island Hopping)

During our weekend at Abba’s, we spoke about Decoy Pigeon, artifacts, and cultural mapping efforts of the Samal Tourism Office. They hope to establish a small museum and release a publication about the history and culture of Samal, however, they currently don’t have enough people to handle the tasks.

On Abba’s recommendation, Curtis and I visited Sanipaan Marine Park, commonly called Vanishing Island. The mangrove sandbar emerges from the Gulf of Davao at low tide and disappears at high tide.

July 03-07, 2023

Mica:

Subangan Museum was recommended by a few people, so we made our way to Mati, Davao Oriental to view the collection, meet another artist friend AJ Omandac, and spend a few days on Dahican beach. Dahican was quiet when we arrived. A few locals told us the governor had just died and the town was mourning, although we weren’t sure whether the general lack of activity was due to communal grief or the low tourist season.

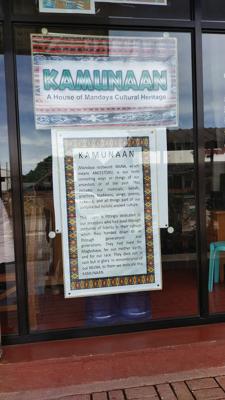

At the gate of Subangan Museum, we learned the museum was closed for the whole week because museum personnel were in Cateel, a municipality north of Mati. We decided to explore the town and ended up in a cafe near the boardwalk, where we also passed Kamunaan: A House of Mandaya Cultural Heritage. The showroom was run by a local NGO promoting Mandaya culture, and while the neighboring tribal group was not included in the scope of Decoy Pigeon, we saw a few weapons and armrings similar to the Bagobo items in Lot 1913/26.

July 05, 2023

We don’t know how RJMs collections were obtained originally, other than the exchange that took place with Leiden, nor do we know the terms or transparency presented to the original owners of the artefacts. But we’re left wondering things like:

Did the original owners know that their items would end up in a museum?

Did they know that an organisation would eventually profit from having obtained the items?

Were they offered information on what would happen to them at all?

Were the items taken with force, or collected from the remains of a community?

Were they able to contribute any context to the original purpose or use of the items?

Did they know how their community might be portrayed to those who interact with the items in the future?

Were duplicates of the items obtained purposely to hoard and then exchange in the future?

Were they taken home and trophied by their collectors as a medal of exotic exploration?

In contrast, throughout our personal experience of collecting for Decoy Pigeon, there were times when an exchange was more valuable to us, and the balance of power was often leaning towards us. Other times we would pass the reins to the other party, and were unaware of where an exchange or simple conversation would lead us, but curious to hear the information that people deemed relevant and interesting.

It seemed as though things like if the values of the items were to increase or not, or how and if we preserve them etc, was not a concern for the people who helped us, and the exchanges were made on more mutual terms, appreciated for what they were, and the time shared, regardless of a presumed value. The vast appreciation of simple conversation regarding the items and the cultures they represent, casts an image of a society that is proud to be associated with their ancestors and the indigenous people of today, while accepting that the presence of colonial residues in everyday life is a part of their identity.

Would it be fair to create a picture of how different The Philippines would be today, had it somehow never been colonised, or colonised by different powers? Or to imagine how much of their heritage and identity would be dominant rather than being exchanged for/diluted by western ideologies? Perhaps it would be better to hear which elements of their colonial past Filipinos identify with or reject, and understand what they would exchange these elements for if they had the choice.

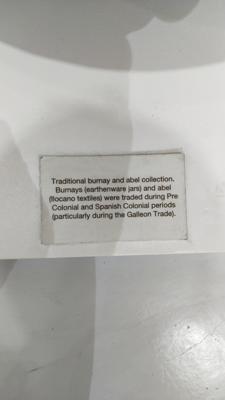

This was one of the first few objects we acquired, found during a short sidetrip to Buscalan Tattoo Village, Kalinga. Although slightly different in cut and design from drinking vessels RJM29814 and RJM29815, such coconut cups are ubiquitous in Luzon and serve a general purpose as a vessel for liquids, food and other things. In Buscalan, these are used to hold charcoal ink for handtap tattoos.

We thought this would be one of the most difficult items to find, but it was surprisingly common and widespread, appearing in several places in Cordillera and Ilocos. On the “Mapping Philippine Culture” website it is labeled as Headhunter’s Ax, although in the RJM inventory it is only beil or ax; in Apayao it is called iku, an Isneg woman’s knife used in agriculture and cooking. The man’s knife, aliwa, has a narrower and more elongated blade.

The aliwa and iku are sometimes framed together and sold as souvenirs or tokens of friendship, like these items at the DTI Pasalubong Center.

The aliwa continues to be a regional symbol in Apayao, with a large statue of it featured in the grounds of the Pudtol municipal hall. The municipal hall also had a collection of small and mid-sized aliwa and iku.

Isagaddan Crafts and Souvenirs continues to manufacture aliwa and iku. The shopkeeper told us that the iku is often used to crack open betel nut (mamah/mommah) for chewing. We purchased one small iku for PhP300 and two wooden iku keychains for PhP50 each.

Iku and aliwa are also in the collection of Museo Ilocos Norte.

There is a similar ax displayed above the entrance of Igorot’s Charm Cafe in Baguio City.

These coconut cups are ubiquitous in Ilocos and Cordillera. The particular item we have is of the exact same form as RJM29814 and RJM29815 and is the most common. We purchased this from Sarusar Souvenir Shop in Museo Ilocos Norte in Laoag City, Ilocos Norte for Php100.

We saw these cups in several collections including the Eco-Tourism Office in Luna/Apayao, Museo Ilocos Norte, MMSU-CTE Taldiap Society Museum and even at a souvenir shop in Lemur and Butterfly Park in Bohol, Visayas.

Our host in Abra, Amarte Escala, recognized this as piningitan cloth. He took us to Leila’s Loomweaving in Bulbulala, La Paz where the cloth is produced. There we met the workshop owner Natividad Quiday, who was wearing the piningitan skirt. We bought a new one for PhP400.

The cloth likewise appears in the collection of the Abraeniana Museum.

Google translates Hüftfederschmuck as “hip feather jewelry”, while “Mapping Philippine Culture” label these as feather headdresses. In the Cordillera region it is commonly worn with a woven headband.

The proprietress at Isagaddan told us that they sometimes carry these, but the items were sold out during the Apayao Day Say-Am Festival in February. She offered to make some for us if we wanted to order.

Jobelle Bocaig of Achilles-25 Store generously gave us a woven headband with feathers.

These also appear in Tam-awan Village in Baguio City as part of native “costumes” that visitors can try on for photographs.

Dave Gatenby recognized this as a textile design made in San Ramon, Manabo, Abra. According to him, the cloth takes 1-2 weeks to produce by order, and thus quite expensive. The design is so complex that a weaver can only finish 10 centimeters a day.

Jobelle Bocaig of Achilles-25 Store remembered encountering the textile just recently, although she didn’t have any in stock in her store. She showed us a photo of herself wearing the fabric.

We found this shield in a small collection at the Eco-Tourism Center in Luna, Apayao.

It seemed likely that Isagaddan Crafts and Souvenirs would also have it, but when asked, the proprietress explained that it was a very old design and they didn’t have any in stock, although they did have more modern designs on hand.

It also appears in the Highlands display of Museo Ilocos Norte.

As a functional object, this comb seemed simple and useful enough to be in contemporary circulation. We expected to find it among backscratchers and other wooden wares in one of the souvenir shops of Calle Crisologo, Vigan; however, we didn’t find a duplicate of this comb anywhere.

Dave Gatenby said we might find this among the handmade musical instruments and bamboo creations of folk musician Elmer Tadeo from Malibcong, Abra.

We found single pipes or ‘pito’ in many souvenir shops and collections in Luzon. A set of panpipes are on display at Museo Ilocos Norte.

Amarte Escala helped us look for bamboo craftsmen who might produce this drinking vessel. A woman at the village we visited told us that she knew an artisan who could make one for us, although it was unclear where this artisan lived.

In a conversation with Dave Gatenby and Dexter Macaraeg, we understood that these bamboo drinking cups do not normally come as multiples, and that this particular object was probably a set of single vessels tied together for convenience or for display purposes. In the jungle, people would simply cut pieces of bamboo to use temporarily for drinking water or alcohol. The bamboo cups could afterwards be disposed of without much negative environmental impact.

We didn’t find information or accounts of carabo horns being used as drinking cups, and this trinkhorn caused some puzzlement among people we showed it to. In a few occasions, we found horn trumpets used for communication and sound signals, which may have been closer to the real purpose of the original item. We found a horn-pouch being sold as a novelty at Sarusar Souvenir Shop in Museo Ilocos Norte.

We did not stop at Ifugao and so did not have a chance to look for this ornate tobacco pipe in its place of origin. Common tobacco pipes, however, were plentiful in a wide variety of shapes and sizes across Luzon.

This Bagobo blade with woven sheath is a prized artifact, according to Joyce at Omar Souvenirs in Poblacion Market Central, Davao City. The Bagobo very rarely make these knives with intricate woven pouches anymore, unlike their neighboring tribes who continue to produce weapons, ornaments and brass wares. Such objects can fetch good prices at souvenir shops and antique stores like the ones in Poblacion Market Central. When the Bagobo ‘farmers’ do come to the shop with their knives, Joyce added, they are very quickly bought by collectors.

Similar knives with sheaths are on display at the Davao Museum of History and Ethnography.

During our trial round of collecting in Buscalan Tattoo Village, we purchased a souvenir knife with sheath keychain, also common in souvenir shops in Luzon.

The titular object was so elusive and so closely tied to a particular practice that nobody we spoke to recognized what it was. Perhaps a first-hand consultation with Bagobo elders would have yielded a more illuminating and specific result.

A keyword search in ethnographic literature turns up mentions of decoys, snares, and wooden birds in Bagobo culture. Likewise, Laura Watson Benedict’s compilation of Bagobo Myths tells of a spirit called S’iring, which imitates a loved one’s voice to lure and trap its victims.

In Museo Ilocos Norte, we found an intriguing object called kurkurita or octopus lure from the coastal town of Currimao in Luzon.

These shell armrings or bracelets are common in Mindanao and appear in collections attributed to different tribes. We also found them at D’Bone Collector Museum.

Weapons were common in collections and souvenir shops across the archipelago. However, we spent less time searching for large weapons, knowing that we would not be able to acquire and transport duplicates of them on our travels. Likewise, we did not collect duplicates from the Visayas region because all the Visayan objects in Lot 1913/26 were weapons.

Benedict, L. Estelle Watson. (1916). A study of Bagobo ceremonial, magic and myth. [New York]: [s.n.].

Cole, F., Gale, A. (1922). The Tinguian: social, religious, and economic life of a Philippine tribe. Chicago: Chicago Natural History Museum.

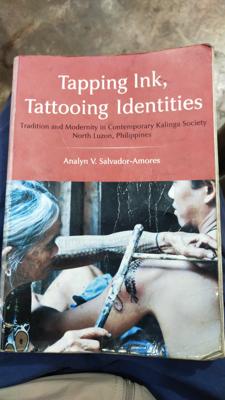

Salvador-Amores, A. V. (2011). Tapping ink, tattooing identities: tradition and modernity in contemporary Kalinga society North Luzon, Philippines. University of Oxford.

Caferiano

Claveria Boulevard, Taggat Norte, Claveria, Cagayan

Buscalan Tattoo Village

Buscalan Proper, Tinglayan, Kalinga

Star Jewel Lodge

Kabugao- Pudtol - Luna - Cagayan Boundary Rd, Luna, Apayao

DTI Pasalubong Center Luna

Provincial Capitol Compound

Kabugao - Pudtol - Luna - Cagayan Boundary Rd, Luna, Apayao

Eco-Tourism Center Luna

Provincial Capitol Compound

Kabugao - Pudtol - Luna - Cagayan Boundary Rd, Luna, Apayao

Isagaddan Crafts and Souvenirs

Poblacion, Pudtol, Apayao

https://www.facebook.com/Isagaddan

Pudtol Municipal Hall

Kabugao - Pudtol - Luna - Cagayan Boundary Rd, Pudtol, Apayao

Cagayan Museum and Historical Research Center

Otis Street cr. Aguinaldo St. Centro 10, Tuguegarao City, Philippines

Natsuca Beach Resort

Sitio Dialao, Brgy. Caparispisan, Pagudpud, Ilocos Norte

Breakfast at IMA Cafe

Sitio Dialao, Brgy. Caparispisan, Pagudpud, Ilocos Norte

OTOP (One Town, One Product) Store

Museo Ilocos Norte

Gen. Luna corner Llanes Streets, Laoag City, Ilocos Norte

https://www.facebook.com/MuseoIlocosNorte

Sarusar Souvenir Shop

(inside Museo Ilocos Norte)

MMSU-CTE Museum

Apolinario Castro, Laoag City, Ilocos Norte

https://www.facebook.com/thectemuseum

National Museum Ilocos

Burgos St, Vigan City, Ilocos Sur

https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/our-museums/regional-area-and-site-museums/ilocos

Calle Crisologo

Vigan City, Ilocos Sur

Vigan Conservation Complex

Liberation Boulevard, Vigan City

Escala Homestay

Mudeng, La Paz, Abra

Leila’s Loomweaving

Sitio Callaguip, Bulbulala, La Paz, Abra

https://www.facebook.com/natyquiday

Abraeniana Institute and Research Center

Divine Word College of Bangued

Rizal Street, Bangued, Abra

Dave Gatenby, Silverbackpacker

Dexter Macaraeg

Achilles-25 Store

Rizal Street, Bangued, Abra

https://www.facebook.com/JUSTICEFORPO3CARLOSBOCAIG

https://www.instagram.com/achilles25store

Ocean Breeze

Baroro, Bacnotan, La Union

Baguio Museum

Gov. Pack Road, Baguio City

Victor Oteyza Community Art Space (VOCAS) and Oh My Gulay Cafe

5th Floor, La Azotea Building, 108 Session Road, Baguio City

Ili-Likha Artists’ Wateringhole

Assumption Road, Baguio City

Tam-awan Village

366-C Long Long Benguet Rd, Baguio, Benguet

Igorot’s Charm Cafe

370 Pinsao Proper, Tam-awan, Baguio, Benguet

https://www.facebook.com/IgorotsCharmCafe

https://www.instagram.com/igorotscharm

https://www.instagram.com/atewamz

Cordillera Museum / Museo Kordilyera

Governor Pack Road, University of the Philippines Baguio Campus, Baguio City, Benguet

https://museokordilyera.upb.edu.ph

https://www.facebook.com/upbmuseokordilyera

Pugad ni Art Studio

211-B Sitio Atol, Puguis, La Trinidad, Benguet

Center for Kapampangan Studies

Holy Angel University

#1 Holy Angel St, Angeles, Pampanga

https://www.hau.edu.ph/advocacies/center-for-kapampangan-studies

Lemur and Butterfly Park Bohol

Villalimpia, Loay, Bohol

https://www.facebook.com/p/Bohol-Lemur-Butterfly-Park-100083284115366

Petit Coin de Paradis

Poblacion, Alcantara, Cebu

Eskapo Verde

Santander - Barili - Toledo Rd, Barangay Bugas, Badian, 6031 Cebu

Cinematheque Centre Davao

Teodoro Palma Gil St, Poblacion District, Davao City, 8000 Davao del Sur

D’ Bone Collector Museum

76-A San Pedro St, Poblacion District, Davao City, Davao del Sur

Poblacion Market Central

C. Bangoy St, Poblacion District, Davao City, 8000 Davao del Sur

Omar Souvenir

Poblacion Market Central, Davao City

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100093964143792

Nurlika’s Souvenir Shop

https://www.facebook.com/JNASweetTreatsDavao

Davao Museum of History and Ethnography

Zonta Building, 113 Agusan Circle, Insular Village 1, Lanang, Davao City, Davao Del Sur

Sanipaan Marine Park (Vanishing Island)

Barangay Tambo, Samal Island, Davao del Norte

Subangan Museum

Surigao-Davao Coastal Road, Mati, Davao Oriental

Amihan sa Dahican

Dahican Bay, Mati, Davao Oriental

Kamunaan House of Mandaya Heritage

Bonifacio Street, Mati, Davao Oriental

Curtis and Mica would like to thank:

and everyone who showed us hospitality and kindness during our travels.

All photos were taken by Adaptive Radiations Working Group (Mica Cabildo and Curtis Cresswell).

All texts were written by Adaptive Radiations Working Group (Mica Cabildo and Curtis Cresswell).

—Igorot Charms Cafe—Baguio City.JPG)

—Coconut cup (Trinkgefäß)—Kalinga/Readme/6b18a51bc6f7ff3981bd0a32d240862ee0907a13.jpg)

—Coconut cup (Trinkgefäß)—Kalinga/Readme/275729bdc58bdf688b1ff8dac347a89b0040874f.jpg)

—Coconut cup (Trinkgefäß)—Kalinga/Readme/2155826b73c18dd081c675f85bc503d506d82f8a.jpg)

—Iku (Beil)—Apayao/Readme/c10b9802e35deb4fc980d27e99623293b28d5ed8.jpg)

—Iku (Beil)—Apayao/Readme/46a353abecd673f52a30e01622943feef1ce9eac.jpg)

—Iku (Beil)—Apayao/Readme/3c76e03752e91167ffc1ebf0b94ff4d170fad55e.jpg)

—Iku (Beil)—Apayao/Readme/4d5378e35e0dd01a0901478d0abd021653b8a7e9.jpg)

—Iku (Beil)—Apayao/Readme/3e10d8aec5e4a007aabee7cfe5cde6c436384147.jpg)

—Iku (Beil)—Apayao/Readme/43a980d85cd85cb277bb4226b0a73ff55f4da44c.jpg)

—Iku (Beil)—Apayao/Readme/e2c6cb4fc6f238c07cf3d9507b559316dd9f4c15.jpg)

—Iku (Beil)—Apayao/Readme/56170bdbd2e5de9f357479ae8d178073d777c80b.jpg)

—Buyubuy (Trinkgefäß)—Ilocano/Readme/d60c19e8621f03fb8ab43d3cd731dae36dbdce92.jpg)

—Buyubuy (Trinkgefäß)—Ilocano/Readme/3ffe0e0bdad6312f1286d6fdecc2c4d67c7a4744.jpg)

—Buyubuy (Trinkgefäß)—Ilocano/Readme/a9445425dfcde673df5bb400bbdcb30e828a8197.jpg)

—Buyubuy (Trinkgefäß)—Ilocano/Readme/d062418b324074c0c58cb1ce932d6b9ffd79c1d6.jpg)

—Buyubuy (Trinkgefäß)—Ilocano/Readme/57b5aef524558f999f7b0d325feeb0c4310a0573.jpg)

—Buyubuy (Trinkgefäß)—Ilocano/Readme/25a5a818307279801d81561ce7d579a33fee4cfb.jpg)

—Buyubuy (Trinkgefäß)—Ilocano/Readme/8eb2a684865e0f88f468dcab0fbdd8cc50a38d40.jpg)

—Piningitan (Tuch)—Tinguian/Readme/4cbe64dd72678a3a124067809a8c9e22bf0c812d.jpg)

—Piningitan (Tuch)—Tinguian/Readme/1781eccb835efcb246698d068f8734765791e192.jpg)

—Piningitan (Tuch)—Tinguian/Readme/a2b96e8767ac7c7468b542cdc38a1d44b93dfa4e.jpg)

—Piningitan (Tuch)—Tinguian/Readme/5d07b9114946839b8af064f2f826ef0f17feba33.jpg)

—Piningitan (Tuch)—Tinguian/Readme/7871f6ace3ddcce6d0a7197b6d4555812c1c0560.jpg)

—Feather headdress (Hüftfederschmuck)—Tinguian/Readme/10f58de4aa578fe8d6396308d0c6fc991a4a7c86.jpg)

—Feather headdress (Hüftfederschmuck)—Tinguian/Readme/42e7e05df9b3b7c424f5d5efeaddec10484579e3.jpg)

—Feather headdress (Hüftfederschmuck)—Tinguian/Readme/3b1ad3ddf3c3bdb3a77967912639d552396016ea.jpg)

—Feather headdress (Hüftfederschmuck)—Tinguian/Readme/9afb2b9d6e6592226c4826d258bc4444671e09d8.jpg)